THE FENIAN RISING IN CORK

SOME

BIOGRAPHICAL DETAILS OF CORK FENIANS

Extracts From

JOHN DEVOY'S

'RECOLLECTIONS

OF AN IRISH REBEL'

(Published in New

York, 1929)

JOHN DEVOY (1842-1928), born in Kill, Co. Kildare. Prominent Fenian organiser. Imprisoned 1866-70, pardoned on condition of exile. Spent the rest of his life in the US where he remained active and prominent in the Irish independence movement until his death in New York. Founder of Clan Na Gael.

|

|

See also

Fenianconspiracy 1866

Fenian Rising Part I

Fenian Rising Part II

Fenians

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

THE FENIAN RISING IN CORK

CHAPTER XXIX - THE FIGHTING IN CORK. - FULLY 4,000 MEN, MOSTLY UNARMED, TURNED OUT IN THE CITY –THEIR OPERATIONS CONSISTED ONLY OF ATTACKS ON POLICE BARRACKS - ALL ATTEMPTS, EXCEPT ONE, FAILED – “THE LITTLE CAPTAIN" AND HIS MERCIFUL TERRORISM.

"REBEL CORK" did its best on the night of March 5, 1867, but its best, owing to lack of arms, amounted only to attacks on some police barracks, all of which, except one, failed. I was told by Corkmen after my release, as well as by young COUGHLIN (1) in Millbank, that 4,000 men turned out in the city, but they had less than fifty rifles and no American officer of rank or experience was assigned to the command, except COLONEL JAMES MORAN (then a Captain), was put in charge of Mallow.

At Ballyknockane, a few miles from the city, JAMES F. X. O'BRIEN (2), a civilian and a clever man, but without any military knowledge, was in command, and his chief lieutenant, WILLIAM MACKEY LOMASNEY (3), had served as a private in the Union Army in the Civil War. LOMASNEY had considerable military ability, but was an extremely modest man who never asserted himself and he obeyed O'BRIEN'S orders implicitly. But all those who took part in the fight, with many of whom I talked in New York, agreed that the capture and destruction of the barrack was due entirely to the work of "The Little Captain", as the boys called him.

Curtis's History of the Royal Irish Constabulary, apparently written for the sole purpose of puffing the Peelers and giving them entire credit for putting down the Rising, begins every account of a skirmish with the statement that "a large body of well armed Fenians" attacked the police barrack and were gallantly repulsed by the policemen. There was no "large body of well armed Fenians" anywhere in the Rising of 1867. The Fenians were almost wholly without arms everywhere and the wonder was that they turned out at all. It was generally said that the men were told that arms would be distributed after they turned out, but I could never find any proof of this. The idea seemed to be that the arms captured from the police would enable them to hold out until a shipload, with a covering force, was landed from America. The shipload was sent, but arrived off the Irish coast too late to be of any use, and the vessel was obliged to return to America. The police as a "reward" for the defence of their barracks in 1867, were thereafter styled the "Royal Irish Constabulary".

A fight in a barroom, or the rumour of a divorce would get more space in the New York papers than the whole Rising obtained in the leading Dublin journal of the day, and the news was always at least a day late, the paper evidently waiting for the Castle to supply it. Yet at that time several of the Managing Editors, City Editors and nearly all the crack reporters on the leading New York daily papers were born Irishmen, showing that it was not lack of journalistic talent in the race, but absence of spirit and enterprise in the management, and toadying to or fear of the British Government, which was responsible for the meagre reports. It was a demonstration of the crying need for a revolution.

The following brief paragraphs In the Freeman of March 7, 1867, and following days, are all the paper published (with the exception of a few lines on Knockadoon) about the Rising in Cork:

“Large numbers of the Insurgents assembled in a suburb of the city known as Fair Hill and marched north, tearing up the railway rails at Rathduff. This party was supposed to be marching on Mallow Junction.

"Shortly after two in the morning a large body of Insurgents attacked the police barrack at Midleton and were repulsed. They then proceeded towards Castlemartyr and on their way they fell in with a patrol of four police. The constable in charge was shot dead, another wounded, and the other two made prisoners. On reaching Castlemartyr they immediately attacked the police barracks and were repulsed, leaving their leader dead on the field.

"The police station at Burnfort between Blarney and Mallow was sacked and burnt."

And the paper didn't contain one word about Ballyknockane until March 11, doubtless because it was a Fenian victory and the police didn't want to give it out. Immediately following the little paragraphs about Cork, the Freeman of March 7, under the headline "Precautions at Powerscourt" had the following:

"One hundred Marines arrived at Powerscourt this evening, 10th March, to protect the mansion from a Fenian invasion. It is understood that the force was granted at the special request of Lord Powerscourt.”

The Lord Powerscourt of the day was very unpopular, but his residence was as safe from attack as the beautiful waterfall near by. Not one of the residences of the gentry was molested anywhere during the Rising, though some lead had been stolen from the roofs to make bullets in preparation for it. There was absolutely no looting, no woman was insulted, and even the most notorious "felon-setters" were left unmolested. The nearest approach to looting was the commandeering of the bread from a baker's cart in Thurles, and that was done in the name of the Irish Republic.

As the Peelers resisted stubbornly at Ballyknockane, though their fire inflicted but few casualties as the Fenians fired from cover, Lomasney took a small detachment to the rear of the barrack, smashed a window, threw in some lighted straw and piled in more to feed the flame. This soon smoked the policemen out, set fire to the building, and they surrendered. They were held prisoners for a time after being disarmed until it was considered safe to set them free. Although the Fenians were in strong force, their lack of arms made it impossible to face regular soldiers and the spot was too close to Cork, where there was a large garrison, to risk delay. Detachments were sent to attack other nearby police barracks, but the attacks all failed and O'Brien decided to disband his men and sent them back to the city while it was possible to get in.

Following is the report in the Freeman of March 11 of the Ballyknockane fight on March 5:

"Ballyknockane, Mallow.

"A party of Fenians marched out from Cork to Ballyknockane, which is six miles from Mallow. There were five policemen in the barrack and when summoned to surrender they refused. A volley was fired at the windows and the police replied, wounding one man. The Insurgents then forced the back door and set fire to the place, and compelled the police to come out and their arms were taken from them."

WILLIAM N. PENNY (a Protestant), who was for many years Editor of the New York Daily News, was at that time foreman printer of the Cork Southern Reporter, a bigoted Tory organ, and he told me that the compositors, one after another, came to him on March 5 and asked for a day off on various pretexts. One had a sister who was getting married, another wanted to attend his aunt's funeral, another's father was sick, and so on. Penny lived north of the city and as he was going home very late that night he was halted and questioned by detachments of soldiers, but when he told them he was employed by a staunch Loyalist paper he was allowed to go his way. Late next day he learned of the capture and burning of Ballyknockane police barrack and that accounted for all the weddings and funerals. The proprietor of the paper, a stern old Tory, was in a furious temper and ordered him to "discharge every one of the damned blackguards" and Penny told him he would. Next day the printers began dropping in, looking tired and sleepy, and Penny asked them with a wink if the weddings and funerals had come off satisfactorily and they all answered in the affirmative. He told them of his orders, warned them to be. very careful, and told them they must all take new names. He put "every one of the damned blackguards" back to work and the bigoted old proprietor knew nothing of the trick.

Penny was a member of the Reception Committee which welcomed Parnell and John Dillon to New York, was an active member of the Land League and later joined the Clan-na-Gael, of which he was a member when he died some years ago. He was one of the founders of the New York Press Club and his funeral was very largely attended. There were prominent newspaper men, politicians, business men, Masons, Clan men, actors and literary men there, in great numbers, and two or three old Cork printers who were in the Rising of 1867.

In Mallow only six men turned out, including a brother of WILLIAM O'BRIEN (4), whom he erroneously, in his Recollections, places with the party that attacked Ballyknockane. Colonel Moran assured me he was with him. This group being so small, Moran hoping to meet another contingent, proceeded to Kanturk, where they put up at Johnson's Hotel. Johnson was an Englishman married to an Irishwoman and had been a long time in Ireland. He went into Cork on his jaunting car the next day and brought back the news of the failure of the Rising everywhere, and later facilitated Moran's escape to America. His son was later a member of the reorganized I. R. B. and prominent in the Amnesty movement. The old man was one instance among many of Englishmen settled in Ireland rendering service to the National Cause.

Captain Moran joined the Rhode Island Volunteers in August 1861; he saw nearly two years' service In the [ U.S.] Civil War; had commands at Fort Armory and Hatteras Inlet, N. C., and later at Forts Foster and Parke, at Roanoke Island. But what could an able officer like him accomplish under the conditions at Mallow in 1867? After returning to America, he continued his military activities and was Colonel of the 2d Regt. Infantry (Rhode Island) from 1887 to 1898 when he resigned.

WILLIAM MACKEY LOMASNEY was one of the most remarkable men of the Fenian movement. A small man of slender build, who spoke with a lisp, modest and retiring in manner, one who did not know him well would never take him for a desperate man, but no man in the Fenian movement ever did more desperate things. He was better known in Cork for his raids for arms In Allport's gunshop and other places after the Rising, than for the part he played at Ballyknockane. They were done in broad daylight and he showed great coolness and daring. When he was arrested he shot the Peeler who had seized him. The Peeler, although severely wounded, did not die and Lomasney was tried for attempted murder. Judge O'Hagan, who had been a Young Irelander and later became Lord Chancellor of Ireland, was the trial judge and undertook to lecture him on the enormity of his crime, but Lomasney turned the tables on him by reminding him that he was himself once a Rebel and that he (Lomasney) was only following the example O'Hagan had set In 1848.

The Peeler, a big, powerful man, had knocked Lomasney down and had him under him while they were struggling for possession of Lomasney's revolver. It went off in the struggle and Lomasney had no intention of killing him. O'Hagan was stung by Lomasney's sharp rebuke and imposed a sentence of fifteen years' penal servitude, for which he was severely censured by even the English and the Tory Irish papers. Lomasney took the sentence calmly, although he had only recently been married. It was in Millbank Prison that I first met him, and we became fast friends.

In America, years later, when the dynamite warfare was on foot, he was warned by the "Triangle" that I was a "traitor" and he must not have anything to do with me, but he told Aleck Sullivan that I was an honest man with a right to my opinions and that he would not obey any order to treat me as a man disloyal to Ireland. Sullivan needed Lomasney to hold his grip on the Executive of the organization, which he controlled, so he let the matter drop.

Lomasney then explained his policy and methods to me, and they were entirely different from those of the "Triangle". He wanted simply to strike terror Into the Government and the governing class and "would not hurt the hair of an Englishman's head" except in fair fight. We then discussed the policy fully and I told him the most he could expect through Terrorism was to wring some small concessions from the English which could be taken back at any time when the Government's counterpolicy of Terrorism achieved some success. Lomasney admitted this, but contended that the counter-Terrorism would not succeed; that the Irish were a fighting race who had through the long centuries never submitted to coercion; that their fighting spirit would be aroused by the struggle; that the sympathy of the world would eventually be won for Ireland, and that England could not afford to take back the concessions, which could be used to wring others, and that in the end Ireland would win her full Freedom.

I freely admitted that if honestly carried out on his lines the policy of Terrorism might succeed, but that I utterly disbelieved in the sincerity of those men who were directing it; that they were only carrying on a game of American politics, using the bitter feeling of Irishmen here to obtain control of the organization and turn it into an American political machine to achieve personal purposes. I pleaded for a broader policy that would win the intellect of the Irish at home and abroad and make the race a formidable factor in the counsels of the world, and an ally worth dealing with in England's next big war I further pointed out to him that the temper of the race would upset all his ideas about "not hurting the hair of an Englishman's head"; that once their blood was up the honest fighting men who would have to carry on the work would kill all the Englishmen they could and that England, having the ear of the world and control of all the agencies of news supply, would see to it that the world was duly shocked.

I wasted my time and made no impression whatever upon him. He was as cool and calm during the argument as if we were discussing the most ordinary subject and, while his manner was animated, there was not the slightest trace of heat or passion in it. He even denied the right of the Home Organization to decide the policy for the whole race when I told him the Supreme Council was as firm as the Rock of Cashel against anything being done within its jurisdiction of which it did not fully approve. He was a fanatic of the deepest dye, and all the harder to argue with because he never got heated or lost his temper.

Such was the man who was blown to atoms under London Bridge with his brother, his brother-in-law and a splendid man named Fleming, a short time after my talk with him. The explosion only slightly damaged one of the arches, and I have always believed that this was all he intended to do. He was, in my opinion, carrying out his policy of frightening the English Government and England's Ruling Class. And that it did frighten them, as all the other dynamite operations did, there can be no reason to doubt.

Notes

(1) COUGHLIN/COUGHLAN, JOHN, of Cork city. Apprentice silversmith. Wounded at Ballyknockane. Captured and sentenced to five years. Met JOHN DEVOY at Millbank Prison in England.

(2) BRIEN, JAMES F. X. (d. 1905), born Dungarvan, Co. Waterford. After the Rising, he was sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. Reprieved and sentenced to life. Amnestied, later becoming Nationalist MP for Cork.

(3) LOMASNEY, WILLIAM MACKEY(1841-1884) AKA CAPTAIN MACKEY, born in Cincinnati, Ohio of Co. Cork parents. Amnestied in 1871 and returned to Detroit, in the US, but remained active in the Irish independence movement.

(4) O BRIEN, WILLIAM (1852-1928), born Mallow, Co. Cork. Journalist and Nationalist MP for various Cork seats 1883-95 and 1900-18. His brother JAMES O BRIEN took part in the Fenian Rising in Mallow.

CHAPTER XXX.

KNOCKADOON AND KILCLOONEY WOOD.

COASTGUARD STATION CAPTURED WITHOUT FIRING A SHOT - PETER O NEILL CROWLEY'S TRAGIC DEATH IN A RUNNING FIGHT WITH BRITISH SOLDIERS - HONOURED AS A MARTYR.

The capture of the Coastguard Station at Knockadoon, some ten miles from Youghal, County Cork, by CAPTAIN JOHN MCCLURE and PETER O'NEILL CROWLEY, on the night of March 5, 1867, was the neatest job done by the Fenians in the Rising. It was taken by a well planned surprise, without the firing of a single shot or the shedding of one drop of blood, the ten Coastguards were made prisoners and their rifles appropriated. But it was followed by the tragic death of O'Neill Crowley on March 31 at Kilclooney Wood, in a desperate fight with British soldiers. The great outpouring of the people at the funeral was a demonstration of sympathy which the English Government could not well suppress, and aroused Nationalists throughout Ireland.

CAPTAIN P. J. CONDON, who had served in the [U.S.] Civil War in of the regiments of Meagher's Brigade, a native of Cork and a very capable officer, was assigned to command of the Midleton district, but was arrested the day before the Rising. JAMES SULLIVAN, the Centre of the town, and several others were arrested. That disarranged the general plan and broke the connections, so that several contingents did not turn out. Sullivan had previously been several months in Mountjoy Prison, where I met him, and his movements were closely watched after release on bail. Condon's arrest was a severe blow.

Condon was McClure’s brother-in-law, and they had come from America together. O'Neill Crowley, a prosperous farmer about thirty-five years old, was the Centre of the Ballymacoda district. He was a very popular man, and had great influence with the people. His Circle numbered a hundred men, and every one of them turned out. McClure told me they were a fine lot of fellows, but at the outset they had only one rifle (Crowley's own), a few old shotguns, and McClure’s Colt's revolver. There were a few pikes, and some of the men had sharpened rasps, fastened to rake handles with waxed hemp. With that paltry arnament very little could be expected of them, but they did a very creditable piece of work.

On three sides of the Coastguard Station there was a sort of platform made of planks, and on the one in front a sentry paced up and down. The blizzard which played a disastrous part later that night had not yet started.

After carefully examining the surroundings, Crowley's men took up a position in the rear of the station and McClure and Crowley crept silently along the planks on one of the dark sides, stood up close to the front and waited. When the sentry reached the corner McClure gripped him by the collar of his coat, put the revolver to his breast, and whispered to him that if he said a word he would shoot. They then took his rifle and went to the door, which was not locked, the men following silently, opened it and went in quietly. The Coastguards were all lying down and most of them were asleep. The arms rack was beside the door and the rifles were secured at once. The Coastguards were made prisoners and marched toward Mogeely, a station on the Youghal Railway ten or twelve miles away, where they were set at liberty.

McClure’s orders were to move to a spot near the railroad to Youghal, and wait for detachments from other points to arrive. But none came. The first train from Cork was to have been stopped, but after waiting in a small wood on the top of a hillock, the first sight that greeted their eyes about dawn was the Cork train moving slowly along. It stopped and a Flying Column of English soldiers and Peelers, numbering 250 men, got out and headed in their direction. The Fenians were hidden by the trees, but twenty minutes would bring the Flying Column to the spot. McClure and Crowley held a hurried consultation and decided to disperse the men except the ten who had rifles. Every one of the unarmed men before leaving told McClure that as soon as he could get rifles for them they would join him again, and all started for their homes. Not one of them was arrested.

The twelve men then started for a spot which Crowley knew as a good hiding place. It was a hill with a plateau surrounded by trees at the top. After placing sentries on watch they lay down and had a good sleep. It was a lonely section of country with no houses within miles, and they remained there in perfect safety for ten or twelve days, and in the meantime were joined by EDWARD KELLY, a New York printer, who had come over for the fight a year previously. He had been with another party which failed, and he had a rifle. Later they were joined by a brother of John Boyle O'Reilly, another printer, who had had a similar experience to Kelly's. Crowley, disguised, went into Cork to get the news, and got back safely. McClure fully expected an expedition from America, but when Crowley brought the news it was that the Rising had failed everywhere and there was nothing about an expedition from America. Yet, they resolved to remain there till something would turn up. They were very comfortable in a dilapidated old house, and were living on the fat of the land. They had plenty of chicken and game, and one of Crowley's men secured some cooking utensils from a family he knew some distance away.

One morning early their sentry reported that he saw what he thought to be redcoats in the distance. The hill they were on commanded a view of the surrounding country for many miles, and in a few minutes they saw three Flying Columns, composed of Military and Constabularymen, converging on their little camp. It would be madness to think of fighting several hundred soldiers and Peelers with a dozen men, so McClure told the boys to disperse and make their way home. As they knew the country very well, they all managed to reach their homes in safety. O'Reilly, who didn't know the country, got away safely also, and was not arrested. I don't know whether the rifles were saved or not.

McClure, Crowley and Kelly started for Kilclooney Wood, but after walking a few miles Kelly's feet gave out, and they had to leave him lying at the back of a ditch. He was arrested, tried, and convicted, and remained in prison for several years. He died in Boston many years ago, and, as he was a Protestant, was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery, in the Roxbury district of Boston, where John Boyle O'Reilly erected a monument in the form of a round tower to his memory. The stone of which the monument is built was brought from Ireland.

Crowley and MccClure reached Kilclooney Wood, but were soon confronted by a soldier, who shouted to them to halt and give the countersign. Crowley levelled his rifle and fired at him, saying: "There's the countersign for you." The bullet did not hit the soldier and they were fired on from several points at once. The wood was filled with soldiers, evidently searching for them. The two men turned in other directions several times, but every time they turned they found soldiers in front of them, not in military formation, but scattered singly. Every soldier who saw them fired, and at last Crowley was hit and severely wounded. Evidently several bullets struck him, but not one hit McClure.

They could have escaped the bullets in the beginning of the running fight by surrendering, but neither had the slightest thought of doing so. Shortly after Crowley was hit they reached the edge of the wood where they attempted to cross the Ahaphooca stream which skirted it. Crowley was weak from loss of blood, and in the stream McClure had to put his left arm around him, as his legs were fast weakening. He was six feet two in height, broad-shouldered, deep-chested, and very powerfully built, and in his efforts to hold him up McClure, who was only five feet seven, but strongly built, had to stoop, so that the revolver in his right hand dipped into the water and the old-fashioned paper cartridges with which it was loaded got wet. But McClure, in his excitement, didn't know it. Soldiers and policemen came running up on the outer bank of the stream, with a magistrate at their head, and the magistrate, who wore top boots, stepped into the water and called on McClure to surrender. McClure pointed his revolver at him and pulled the trigger, but, of course, it didn't go off, because the ammunition was wet. He was speedily overpowered and dragged up on the bank. Crowley was lifted up and placed lying on the bank, and it was at once seen that his wounds were mortal.

The English forces were accompanied by Mr. Redmond, Resident Magistrate, who was a retired Captain of the British army and an uncle of John Redmond.

Dr. Segrave, the military surgeon, on examining Crowley, found that he could live but a short time. "Can I do anything for you?" asked Segrave. Crowley requested to see a priest, and mounted-constable Merryman was hastily despatched to Ballygibbon. He was fortunate enough to meet Father T. O'Connell, the curate of Kildorrery, as he was proceeding to his church to celebrate Mass.

In a letter written twenty years later, under date of April 5, 1887, to a local newspaper (the clipping from which reached me in July, 1928), Father O'Connell wrote:

"On my arrival at Kilclooney Wood I found Dr. Segrave, surgeon to the flying column, busily engaged staunching the fatal wound with one hand, whilst from a prayer book in the other he read aloud at the young man's request, the litany of the Holy Name of Jesus. I was deeply touched by the scene, and especially by the exclamation 'Thank God, all is right now', and then turning to the doctor, he said 'Thank you very much, the priest is come; leave me to him'. I saw at once the critical condition of the heroic soul whose life-blood was ebbing fast away. It was clear there was no time to waste; and having made him as comfortable as circumstances would permit, by means of the soldiers' knapsacks, I then, surrounded by the military and police, administered the last sacraments."

The prayer book from which Dr. Segrave read was found in one of Crowley's pockets.

CROWLEY'S dying words as quoted by Father O'Connell were:

"Father I have two loves in my heart—one for my religion, the other for my country. I am dying to-day for Fatherland. I could die as cheerfully for the Faith."

An account of the Kilclooney fight which I published in the Gaelic American in 1904, confirms the foregoing. Crowley died while being conveyed to Mitchelstown.

There is one passage in Father O'Connell's letter to which I take exception. It reads:

"To hold him up as a contumacious Fenian would not be fair, for he had died long before Fenians as an oath-bound and secret society were formally condemned by the Church. I write from thorough conviction when I say that Peter O'Neill Crowley under no circumstances would willingly become a disobedient child of the Church."

His implication that Crowley would not have participated in the '67 Rising if the Pope's condemnation of Fenianism had been issued sooner, has no justification whatever. The Papal Rescript condemning the movement was issued more than two years before the Rising and Crowley, as a reader of the Irish People, knew all about it, though it was not promulgated in the Diocese of Cloyne.

Crowley's body was given up to his family by Redmond, and he was given a great funeral. He was buried at Ballymacoda, where there is a monument to his memory. All Cork seemed to be there. People flocked to the wake and funeral from all parts of the biggest county in Ireland, and it was an imposing Nationalist demonstration.

O'Neill Crowley was honoured as a martyr, and his name is still revered by Irish Nationalists everywhere. Cork is particularly proud of him. Many people wanted the name of Kilclooney Wood changed to Kilcrowley Wood. Some of them continued to call it by that name for many years, and pilgrimages were made to it on March 5 by the reorganized I. R. B.

PETER O'NEILL CROWLEY was one of the best men in the Fenian movement, and Ireland never gave birth to a truer or more devoted son. His devotion to the cause of Irish Liberty was sublime, and his courage was dauntless. He led a pure life, was a kindly neighbour, and had the respect of all who knew him. I knew a cousin of his in New York named O'NEILL, who was one of the party that captured Knockadoon, and who joined the Napper Tandy Club of the Clan-na-Gael soon after landing. He returned to Ireland and died there. I also knew some other men of the party.

O'Neill Crowley was a deeply religious man. He had taken a vow of celibacy, McClure told me. Father O'Neill, an uncle of his, was flogged by the Yeomen In 1798. JOHN CULLINANE, one of the attacking party, was in New York when we landed, and often came to see McClure, whom he worshipped. Cullinane died at home in Ireland at eighty-eight years of age, in April, 1928, and his imposing funeral was a fitting tribute to the old Fenian.

McClure and I were close friends in Chatham Prison, where the two of us were brought together from Millbank in 1869, and he told me the whole story. His account of the incidents after the surrender at Kilclooney differs in a few details from other versions, but that can easily be accounted for by the fact that he was a prisoner at the time and could not see and hear everything that then transpired.

An officer of the New York Clan-na-Gael (President of the old Sarsfield Club) named Anthony Fitzgerald, went home to Cappoquin, County Waterford (his native town), in the mid-'Seventies, and frequently met Resident Magistrate Redmond there, and they often went over the story of Kilclooney Wood. Redmond said of McClure, with every evidence of admiration: "He was the pluckiest devil I ever saw." McClure thought he would be hanged and preferred to die fighting. He was sentenced to death, but was reprieved and the sentence changed to penal servitude for life. He was released with the rest of us in 1870, and came to New York with the first batch of five in January, 1871.

John McClure was born in Dobbs Ferry, a. few miles up the Hudson from New York, of a Tipperary mother and a Limerick father. When the Civil War broke out he was too young to be accepted as a recruit, but later enlisted as a private in a New York cavalry regiment, and served during the last two years of the war. He was in none of the big battles because his regiment was operating in the Blue Ridge of Virginia against Mosby's Guerillas, but was in numerous small fights. Patrick Lennon, who led the Fenians at Stepaside and Glencullen, was engaged in the same work at the same time, but they never met until after their release from prison.

McClure was rapidly promoted and was made a Lieutenant for gallantry in action at the age of twenty. He was only twenty-two in the Rising. He married Miss Mary Flanagan, whom he met at the house of Thomas Francis Bourke's mother, a couple of years after his return to New York. He had two brothers, the eldest, William J., being a priest, who published a volume of poetry, and the youngest, David, was a lawyer, who became prominent at the New York Bar. John was Chief Clerk in David's law office. All the McClures are dead at this writing.

__________________________________

__________________________________

SOME BIOGRAPHICAL DETAILS OF CORK FENIANS

'…The chief recruiting grounds in the Capital were the trade unions and the three big drapery establishments, Cannock, White & Co.; Todd, Burns & Co., and McSwiney, Delany & Co. In these establishments the Drapers' Assistants were all country boys and were a fine set of fellows. They were boarded and lodged in the houses where they worked and were obliged to dress well in order to keep their jobs. They were also well-mannered and very intelligent. Several of them, chiefly from Cork, were already members before they left home and were great recruiters.

The man who swore me in, JAMES JOSEPH O CONNELL O CALLAGHAN, of Kanturk, was, next to O DONOVAN ROSSA and Edward Duffy, the best recruiter in Ireland, but he had a great talent for exaggeration…..'

_________________________________________________________________________________

'In Cork City the chief of whom all looked up to was JOHN KENEALY, who was convicted and sentenced to ten years' penal servitude in January, 1866. He was released from Western Australia in 1869, went to San Francisco, where he lived for many years, moved to Los Angeles before it became famous, except as a health resort, and died there many years ago. Although the system of County Centres did not exist in the old organization, JOHN KENEALY practically exercised all the functions of that office for Cork County. He was an even tempered man with a judicial mind and fine judgment, and was highly respected by everybody.

Skibbereen was a hotbed of Fenianism and gave us not only O'DONOVAN ROSSA (whom Padraic Pearse justly described as the most typical Fenian) but MORTIMER MOYNAHAN and his brother, MICHAEL, who later on was Secretary to General Canby during the Modoc War in the Lava Beds, the three DOWNING BROTHERS, P. J., DENIS AND DANIEL. P. J., after serving with distinction in Meagher's Brigade, became Lieutenant-Colonel of the Ninety-ninth New York National Guard (of which JOHN O'MAHONY was Colonel), later settled in Washington, and died there. He was the father of Rossa Downing, well known in the early days of the Friends of Irish Freedom.

There were more prisoners from Skibbereen in Mountjoy Prison in 1866 than from any other town in Ireland. They were mostly Gaelic speakers and spoke English with a very strong brogue. "Have oo any noos from Shkib?" one asked another in my hearing one day as we walked round the exercise ring, and the other replied: "No; but I do be dhraming - wisha, quare dhrames." Owing to the close confinement, prisoners often had distorted dreams.

Next to JOHN KENEALY in Cork City was JAMES F. X. O'BRIEN, a man of considerable literary ability. JOHN LYNCH was another very active member in the early days. He was convicted early in 1866 and died in Pentonville Prison. Another energetic worker was JOHN O'CALLAGHAN, who spent several months in Mount-joy Prison as a suspect in 1866, but was not convicted.

Bantry, Mallow, Fermoy, Midleton and Kanturk were good Fenian towns, but Fermoy came next to Skibbereen in strength. East Cork was poorer in spirit than West Cork, and the people seemed to belong to a different branch of the Race.'

'The principal letter writer to the Irish People was JAMES F. X. O BRIEN, of Cork, who was convicted for his part in the Rising and later became a Member of Parliament. His letters were always long and well written and were signed De l'Abbe.' He had lived in New Orleans for some years and knew French very well.'

_________________________________________________________________________________

'In Cork, a Blackpool boy - where they said 'dis' and 'dat' - went to confession and when the priest asked him if he had taken the Fenian oath he said: 'I did, but what has dat to do wid me confession?' The priest answered: 'Tis an illegal society,' and 'de boy from the Pool' replied: 'Yerra, what does I care about deir illaigal? I tinks more o' me sowl.'

_________________________________________________________________________________

‘No account of Fenianism in the British army would be complete without a sketch of "PAGAN" O'LEARY, who was the first man appointed by James Stephens to take charge of the work. The "Pagan" was a unique character. A fanatic on the question of Irish Nationality and Roman interference in Irish affairs, he was generous and charitable to a fault, and under the disguise of stern looks and harsh words carried a heart as tender as a woman's. His "Paganism" was only a distorted kind of Nationalism.

His real name was PATRICK O'LEARY and he was born in or near Macroom—"in old Ibh Laoghaire by the Hills"—about 1825 or 1826. His age can only be estimated by the fact that in 1846 when the Mexican War broke out, he was a very young man studying for the priesthood in an American Catholic college, the walls of which he scaled to enlist in a regiment going to the front. He took part in several battles and was hit in one of them by a spent ball at the top of the forehead. It left an indention that was quite visible and easily felt with the fingers. This undoubtedly affected his mind to the extent of making him very eccentric.

His eccentricity took the form of a sort of religious mania. He hated Rome and England with equal intensity, and his queer notion was that after driving out the English, Ireland should return to the old Paganism. He was not really a Pagan, but an anti-Roman Catholic. He never talked of the old Pagan worship or beliefs, but was eloquent in extolling the superiority of Tir-na-nOg over the Christian Heaven. He did not seem to doubt the existence of either of them and talked as if a man could make his own choice as to where he would go after death.'

‘The organization in the British army was not started by "PAGAN" O'LEARY. Some "Centres" in garrison towns had sworn in soldiers, and a few men already enrolled had enlisted, but Stephens discountenanced the work of spreading the movement in the army. It was impossible, however, to reach all of those who were doing work in that line, as no record was kept of those who had enlisted. So the swearing in of soldiers went on irregularly, though the number for a while was not large.

Two young teachers from the Skibbereen district of Cork, who had been up for training in the Agricultural School at Glasnevin, had some trouble in the school, and enlisted in the Twelfth Regiment of Foot. Their names were DRISCOLL AND SULLIVAN, and they were both members. They started to work immediately and swore in a good many men in their own regiment and in the Eighty-fourth, both of which were then stationed in Dublin. CON O'MAHONY of Macroom, who was Stephens' secretary, DAN DOWNING of Skibbereen, who was a clerk in the Irish People office, JAMES O'CONNOR and I were walking in the Phoenix Park one Sunday in 1863 when the two young soldiers came along and I was introduced to them. In the course of the talk I found they were quite sanguine about getting the great majority of the Irishmen in the army. They themselves, without money or civilian help, had already sworn in several hundred men.'

'Among the soldiers was THOMAS HASSETT, a Corkman, who had served in the 'Pope's Brigade,' but was then in the Twenty-fourth Foot, and who was afterwards one of the six men rescued from Western Australia by the Catalpa expedition.'

_________________________________________________________________________________

'I heard no more about the Rising until a young Corkman named COUGHLIN, convicted for his part in the fight at Ballyknockane under JAMES F. X. O BRIEN and 'The Little Captain' (WILLIAM MACKEY LOMASNEY), was brought into Millbank [prison] and while working side by side at the pump to fill the cistern on the top of the building told me the whole story of the miserable failure, and the treachery of Corydon and Massey.'

_________________________________________________________________________________

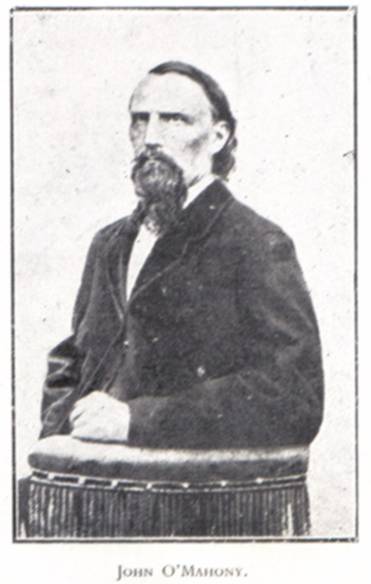

'JOHN O'MAHONY, the leader of the American Fenians—"Head Centre" was the official title—was one of the most interesting characters in Irish history. He was an Irish gentleman of the old school, of splendid physique, well educated, and an accomplished Gaelic scholar. Descended from the Chief of the O'Mahony Clan and recognized as their Chief by the stalwart, fighting peasantry of the mountainous region on the Cork-Tipperary border, he was brought up without any association with "the Garrison", among whom he lived as a "gentleman farmer", with a very comfortable income. His standing among the people was aptly illustrated in a poem by his Secretary, Michael Cavanagh: "Hail to you; hail to you, Chief of the Comeraghs," and he himself, in a lecture in Cooper Institute, New York, some years before his death, described this status by saying that the head of his family "could always count on 2,000 men in his quarrel". That illustrates the Ireland of the Clans. They fought for the Chief whether he had the right or the wrong on his side—and recent events have shown that there is very much of that spirit in Ireland to-day.

O'Mahony was born at Clonkilla, a picturesque place on the banks of the Funcheon, near Mitchelstown, County Cork, in the year 1819.

In the early days of Fenianism, and even earlier, there were many stories current in Ireland regarding the great physical strength and prowess of O'Mahony and his immediate ancestors. The O'Mahony family were the popular champions against "The Garrison", and had many encounters with the latter. An article by Dr. Campion of Kilkenny, describing how O'Mahony's grandfather had horsewhipped the Earl of Kingston, the most powerful landlord in the neighbourhood, for some insulting remarks, appeared in the Celt in 1857. John O'Mahony wrote a letter later correcting some of the details, but confirming the horsewhipping.

The most widely spread of the stories was about O'Mahony's encounter with a "wicked" bull when a young man. He had a habit of vaulting over walls when strolling around and one day he landed in a corner where he found a bull of vicious reputation facing him, with no chance of getting away. The bull lowered his head to charge, but O'Mahony jumped on the angry beast's back, gripped him by the horns, belaboured him with a stout stick and held his place on the bull's back while the animal charged wildly around the field until exhausted. Irish boys are very much influenced by stories of physical prowess, and this particular story gave many a boy the idea that O'Mahony was a hero.

On the outbreak of the abortive Rising in Tipperary, in '48, O'Mahony gathered about 2,000 men, all of fine physique, but with no training or organisation and, with the exception of some fowling pieces, no arms. There had been no Young Ireland propaganda among them and there was probably no Confederate Club in the whole mountain district. The men—all Gaelic speakers—were simply following their Chief to fight the English. That spirit was in the marrow of their bones and needed no propaganda to make it flare up.

But the utter collapse of Smith O'Brien's attempt at Ballingarry and John Blake Dillon's decision not to fight at Killenaule, rendered it absolutely useless for him to keep his men "out", so O'Mahony disbanded them and remained in hiding until he escaped to France. After a short stay in Paris, where he met James Stephens who had also escaped, he made his way to America.

When O'Mahony went "on his keeping", as they called it in those days (1848), he turned his property over to his brother-in-law, one of the Tipperary Mandevilles, and, as he had no professional training, he was dependent for a living on an occasional small remittance from his sister and some pitiful remuneration for literary work. His principal literary effort was a masterpiece—the translation from the Irish of Keating's History of Ireland. Competent judges have said that his notes are almost as valuable as the history itself, on account of his intimate knowledge of old manuscripts and the traditions of the people.

I had the privilege of seeing the manuscript from which O'Mahony made his translation. It belonged to a Corkman named Sheehan who was practicing law in New York, and at a dinner in his house in the mid-seventies he took great pride in showing it to Joseph I. C. Clarke, James J. O'Kelly and me. The transcript of Keating's work had been made by Sheehan's grandfather, whom he described as 'The Southern Captain Rock,' and was very carefully done on vellum. There was not a flaw or an erasure in it.

During the [U.S.] Civil War O Mahony organised a regiment of the New York National Guard (the Ninety-ninth) composed entirely of Fenians, and was appointed Colonel of it. That was how he got his military title. But LIEUTENANT-COLONEL PATRICK J. DOWNING, who had served in Meagher's Brigade, was the real commander of the regiment as O Mahony was too busy to give much attention to it. It did not do any fighting in the war, but was called out for duty to guard Confederate prisoners for many months at Elmira. CHARLES UNDERWOOD O CONNELL, who went to Ireland in 1865 and spent five years in British prisons, was a Captain; John F. Finerty was a sergeant, and Anthony Macowen, for some years Coroner in the Bronx, also served in it. Several of the men went to Ireland in 1865 to take part in the projected insurrection.'

_________________________________________________________________________________

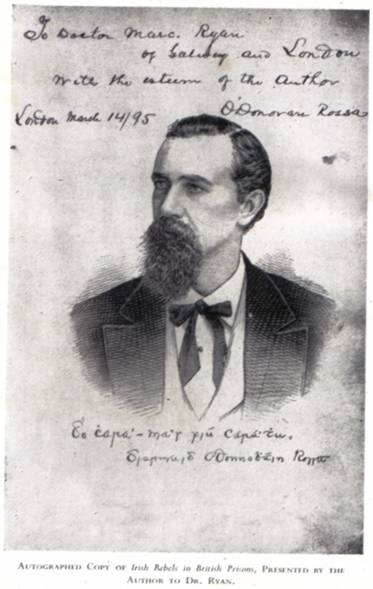

'O DONOVAN ROSSA's career was an epitome of the history of Fenianism. He was the very incarnation of its spirit. He typified more than any other Irishman of modern times the unrelenting hostility to English rule and the implacable determination to get rid of it which were the chief characteristics of the Fenian Movement, as they were of the United Irishmen and of John Mitchel. Mitchel and the United Irishmen were the prophets of Fenianism and no Fenian worshipped more devoutly at their shrines than O Donovan Rossa.'

'As early as 1856 the young men of Ireland had begun to shake off the lethargy that followed the failure of 1848 and the betrayal by the Parliamentarian leaders. Small groups of Nationalists began to organise in various parts of the country. One of these organisations was the Phoenix Society of Skibbereen, of which O Donovan Rossa was the moving spirit. In May, 1858, Stephens arrived at Skibbereen on his tour to spread the I.R.B., which had been established in Dublin the previous March. Rossa was sworn in and soon practically the whole membership had become Fenians. It was because they all originally belonged to the Phoenix Society, which was a public organisation, that Fenianism at that time was generally known as the 'Phoenix Movement,' but its real name then, as later, was the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

As mentioned in Chapter II, Rossa and some of his comrades were arrested in December, 1858, and released the following July. Coming out of prison, he found his business broker up and his family evicted from their home. He kept a shop in which he sold general merchandise, and he had to reorganise the business under difficulties. Before his arrest he had many of the gentry for customers; after his release they all deserted him and their example was followed by the shoneens. A system of terrorism was organised, in which Bishop O Hea, a bitter anti-Nationalist, took a leading part, with the object of frightening away his customers, and the boycott had a large measure of success. The constant persecution eventually broke up his business and he had to come to New York in 1863.

He returned to Ireland the same year and on the starting of the Irish People as the organ of the movement in the following November, Stephens appointed him Business Manager of the paper. From then until the paper was suppressed and the plant seized on September 15, 1865, Rossa was the most active man in the movement in Ireland. He travelled constantly for the organisation in Ireland, England and Scotland, and made one more trip to America. He swore in more members than any ten men in the movement and had a wider personal knowledge of the membership than even Stephens himself.'

'Jeremiah O Donovan Rossa was born in Rosscarbery, County Cork, on Sept. 11, 1831, and claimed to be descended from the Chief of the Clan. There were three separate branches of the Clan, called respectively O Donovan Dubh, O Donovan Buidhe and O Donovan Rossa, all offshoots of the original Sept which had grown so numerous that they separated eventually and became independent of each other. John O Donovan, the great Irish scholar, came of one of these groups, but his immediate ancestors moved to Kilkenny and remained in that county, which at the time of his birth was Irish speaking, as all the Leinster counties were up to the very walls of Dublin. There was hardly a word of English spoken in Rosscarbery when Rossa was a boy, but he learned it at school. I believe it was his father who taught him to read and write Irish, but, whoever taught him, he did both well.

He was apprenticed to a grocer on leaving school and in early manhood was started in business for himself in Skibbereen. He married a Kerry girl named Eager by an arrangement between the parents, according to the custom of the time. She bore him four children, all boys, Denis, John, Jeremiah and Conn.

When his first wife died, Rossa married a Miss Buckley, a tall, handsome girl, the daughter of a prosperous farmer, much against the wishes of her family, who desired to get her a husband of her own class, but the girl was very much in love with Rossa and insisted on marrying the man of her own choice. She was a fluent Irish speaker and she and Rossa always conversed in the old tongue. He had one son by her, who was reared by the Buckleys, because at the time Rossa was in constant trouble and the boy's mother died two or three years after the marriage. The boy died early also.

Rossa's third marriage to Mary Jane Irwin of Clonakilty is so fully described in his "Prison Life" that I need not dwell on it here. Like her predecessor, she was a convent reared girl, very handsome, and she became a very accomplished woman. I met the newly married couple a few weeks after their marriage in 1864 in Abbey Street, Dublin, and was introduced to her by James O'Connor (then the bookkeeper in the Irish People office) as he, Dan Downing of Skibbereen and I were taking a walk. O'Connor had told me of the wedding in a short letter a few days previously, in which he said: "Isn't he the devil's clip to tackle the third?"

While Rossa was not what is generally known as a "lady's man", he was always very popular with women. One day as we were darning stockings in Chatham Prison, Ric. Burke was bantering him on the subject and he explained, "half joke and whole earnest", that the reason of his success was that he had a "ball scare" (a beauty spot) which made him irresistible. Then he opened his shirt and showed us a tiny pink spot, "no bigger than a flea bite", as one of the men put it, and told us that it was born with him. He said that Cuchulain and Diarmuid O'Duibhne had the same mark and that there was an old tradition in Ireland that any man born with the 'ball searc' had all the beautiful women falling in love with him.'

_________________________________________________________________________________

COLONEL RICARD O'SULLIVAN BURKE was by long odds the most remarkable man the Fenian movement produced, and also one of the ablest. The story of his life is in large part the history of Fenianism and reads more like romance than a record of actual facts.

He was the youngest son of Denis and Margaret Burke, and was born at Keneagh, near Dunmanway, County Cork, on January 24, 1838. His father was a civil engineer.

When a boy he was tutored at the local National School, the master of which was a Carlow man named Murphy, who later became master of the Model School in School Street, Dublin, which I attended for several years. Murphy was a dyed-in-the-wool West Briton, and after his two former pupils had been sent to prison for Fenianism he expressed bitter regret at his misfortune in having put two such rebels through his hands.

Young Burke from early boyhood showed military tastes and when the Crimean War broke out, in 1853, although he was only fifteen years of age, he and a number of other boys attempted to join the British army to get to the war. English propaganda at that time made a feature of Russian tyranny in Poland and for a time it was very effective in Ireland. Many young fellows enlisted in the hope that they would have a hand in freeing the Poles. The fact that the French were fighting side by side with the English also had some influence in Ireland, but Poland was not freed, nor was her name even mentioned in the terms of peace. Although he was a tall, well developed boy, his youth prevented his being accepted as a recruit. But he was determined to be a soldier, so he joined the Cork militia, where they did not raise the age question.

When the militia regiment was disbanded at the close of the war, in 1856, he was ashamed to go home, on account of the disgrace attending service in the militia, which was mainly composed of corner boys, tinkers, and other wastrels, so he went to sea. Before long his superior intelligence won him promotion and he became supercargo of a sailing vessel. He "followed the sea" for several years and travelled practically around the world. He visited nearly all the Mediterranean ports, went to Japan, Peru, Chili, Argentina, Mexico, and the United States. He spent about a year in Paris, where he picked up a fair knowledge of French. He also studied art in Paris.

He reached New York for the second time a little before the outbreak of the Civil War and at once made up his mind to enlist in the Federal Army. His sympathies were strongly with the cause of the Union and he was opposed to human slavery. This threw him naturally into the Republican Party and he remained in it to the end, although he was never a politician. He enlisted in the Fifteenth New York Light Infantry, under Colonel John McLeod Murphy.'

'He joined the Fenian Brotherhood in New York before his regiment left for Washington, and helped to organise it in the Army of the Potomac at the front.'

'Colonel Burke's assignment to take charge of Waterford in the Rising [1867], the boarding by him of the Erin's Hope off the Irish Coast, his participation in the I.R.B. convention at Manchester in the late summer of 1867, the successful carrying out of his plans for the 'Manchester Rescue,' and his arrest and detention at Clerkenwell Prison, have already been dealt with.'

'He went through a terrible ordeal at Woking and Broadmoor, and was little more than a skeleton when finally released in 1872. After his release he went to the home of one of his brothers at Coachford, County Cork, where he spent practically his whole time in the open air, fishing and fowling, until his health was completely restored.'

‘The father of Richard Croker (the famous Tammany leader), a County Cork blacksmith, was veterinary sergeant in Burke’s company, and had some knowledge of his people in Ireland. He was a very liberal Irish Protestant, a relative of the famous Crofton Croker, and, while not a Fenian, was in symapathy with the movement. Some time after Burke had moved to Chicago he happened to meet the younger Croker who in the course of conversation asked him what he was doing. Burke answered that he was Map Clerk in the County Clerk’s office in Chicago, and Croker said: ‘Don’t waste your time in a petty job like that. Come to New York and I’ll give you a position worthy of your talents. New York is going to be the greatest city in the world and for many years there will be great construction work requiring able engineers. I’m sure from what my father told me of your ability that you’ll be fixed for life.’ Ric thanked him cordially, but declined the offer.

________________________________________________

© Jean Prendergast 2002 - 2021. All Rights Reserved.

These pages are for the use and enjoyment of website visitors who are researching Cork history and genealogy and they are freely accessible. Some of the material is borrowed from others. Please do not link directly to any images on these pages, as that would constitute misuse.